The Supreme Court Paves the Road for Chattel Slavery in the United States with Trump vs. CASA

How many Rubicons do they have to cross?

The Supreme Court’s decision in the Trump v. CASA case of June 27 (full text here) strips federal courts of the authority to issue universal injunctions—even in cases where policies are unconstitutional—with specific reference to the assault of the Trump administration on birthright citizenship.

The debate in the mainstream media concerns the unfair prosecution of immigrants. Although this aspect of this campaign is not wrong, it is most certainly not the point of this assault on the rule of law.

The attack on birthright citizenship, and the proposal being pushed by agents associated with the Heritage Foundation Project 2025 that anyone at anytime can be stripped of their citizenship, subject to “denaturalization” as Tennessee Congressman Andy Ogles called for in the case of the presumed Democratic candidate for mayor of New York Zohran Mamdani, is an attack on the fundamental constitutional rights of all citizens.

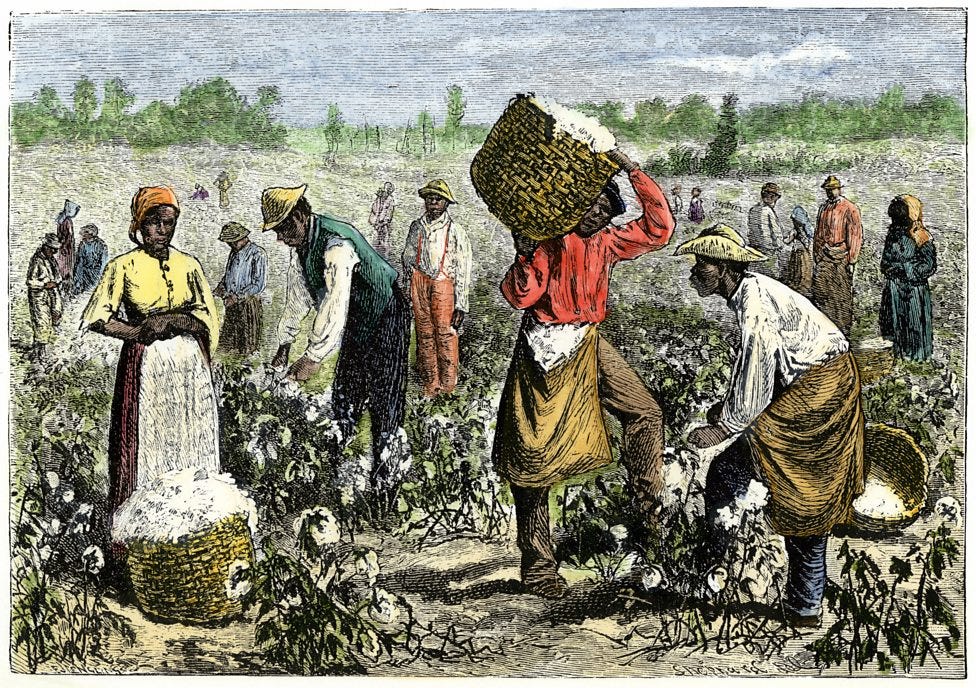

A careful reading of the ruling reveals that Supreme Court’s support of the unconstitutional attack on birthright citizenship is not ultimately about immigrants. Immigrants are just a sweetener for a bitter pill of restricted rights. No, the end of birthright citizenship is the first step towards the reestablishment of chattel slavery in the United States, and the arguments advanced are aimed at not only ending the power of the judiciary to limit the executive, but also at providing an institutional mechanism to make it possible to designate a human as a “non-citizen” with no rights if the government orders it. As WSWS accurately points out in its thoughtful analysis, citizenship is no longer guaranteed and the 14th Amendment ending slavery is no longer in effect.

That is to say that “Trump v. CASA” is the 21st century version of “Dred Scott v. Sandford” (1857) which ruled that those brought from Africa, because they were of “African race,” were not citizens in any sense whether free or enslaved. Here is the specific wording of the Dred Scott ruling:

“A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a ‘citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States.

When the Constitution was adopted, they were not regarded in any of the States as members of the community which constituted the State, and were not numbered among its "people or citizen." Consequently, the special rights and immunities guarantied to citizens do not apply to them. And not being ‘citizens’ within the meaning of the Constitution, they are not entitled to sue in that character in a court of the United States, and the Circuit Court has not jurisdiction in such a suit.”

In the case of the equally heinous Trump v. CASA ruling, the stripping of citizenship is not limited to those from Africa, but can be done to anyone for a crime, for a suspicion of being a threat to national security, or at the whim of the president, the secretaries of state, defense, or homeland security.

I am not sure how many Rubicons we must cross before the sleepwalkers and scaredy-cats will start to awaken and prepare, but I would say this Rubicon is one too many. Seizing immigrants and sending them to a torture prison in El Salvador is the same as kidnapping people in Africa and bringing them to the Carolinas to serve as chattel slavery. There is no difference.

In my presidential platform from 2020 I identified slavery as an essential issue in American society and included it as a plank:

5) 13th Amendment demands the end of slavery

The 13th Amendment of our Constitution explicitly prohibits slavery. Yet our citizens are forced into debt by the dishonest and deceitful actions of banks, the privatization of education, and the spread of slave labor practices through factories and warehouses.

In addition, citizens are thrown in prisons, often on trumped-up charges, and forced to work for no pay under humiliating conditions for the benefit of corporations.

American workers are treated with contempt by multinational corporations that pretend to be American. Even public servants, policemen, and the military are treated as slaves, by the corporations that have seized control of our government. Education and healthcare have been purposely privatized so as to create a population of debt slaves. These despicable practices must be ended, without exception, through the rigorous application of the 13th amendment in the United States.

I also delivered a speech “Forced deportations: Second Step towards a slave society” on April 10th in which I specified how these illegal seizures of immigrants by ICE serve to pave the way for a slave society.

Significance of “DRED SCOTT VS. SANDFORD” (1857)

In this ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a Federal territory.

In 1846, an enslaved Black man named Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, sued for their freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court. They claimed that they were free due to their residence in a free territory where slavery was prohibited.

The odds were in their favor. They had lived with their enslaver, an army surgeon, at Fort Snelling, then in the free Territory of Wisconsin. The Scotts' freedom could be established on the grounds that they had been held in bondage for extended periods in a free territory and were then returned to a slave state. Courts had ruled this way in the past.

However, what appeared to be a straightforward lawsuit between two private parties became an 11-year legal struggle that culminated in one of the most notorious decisions ever issued by the United States Supreme Court. Scott lost his case, which worked its way through the Missouri state courts; he then filed a new federal suit which ultimately reached the Supreme Court.

On its way to the Supreme Court, the Dred Scott case grew in scope and significance as slavery became the single most explosive issue in American politics. By the time the case reached the high court, it had come to have enormous political implications for the entire nation.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney read the majority opinion of the Court, which stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a federal territory. This decision moved the nation a step closer to the Civil War.

The decision of Scott v. Sandford, considered by many legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court, was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

Transcript

DECEMBER TERM, 1856.

DRED SCOTT

versus

JOHN F. A. SANDFORD.

Dred Scott, Plaintiff In Error, v. John F. A. Sandford.

I.

Upon a writ of error to a Circuit Court of the United States, the transcript of the record of all the proceedings in the case is brought before this court, and is open to its inspection and revision.

When a plea to the jurisdiction, in abatement, is overruled by the court upon demurrer, and the defendant pleads in bar, and upon these pleas the final judgment of the court is in his favor--if the plaintiff brings a writ of error, the judgment of the court upon the plea in abatement is before this court, although it was in favor of the plaintiff--and if the court erred in overruling it, the judgment must be reversed, and a mandate issued to the Circuit Court to dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction.

In the Circuit Courts of the United States, the record must show that the case is one in which by the Constitution and laws of the United States, the court had jurisdiction--and if this does not appear, and the court gives judgment either for plaintiff or defendant, it is error, and the judgment must be reversed by this court--and the parties cannot by consent waive the objection to the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court.

A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a "citizen" within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States.

When the Constitution was adopted, they were not regarded in any of the States as members of the community which constituted the State, and were not numbered among its "people or citizen." Consequently, the special rights and immunities guarantied to citizens do not apply to them. And not being "citizens" within the meaning of the Constitution, they are not entitled to sue in that character in a court of the United States, and the Circuit Court has not jurisdiction in such a suit.

The only two clauses in the Constitution which point to this race, treat them as persons whom it was morally lawful to deal in as articles of property and to hold as slaves.

Since the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, no state can by any subsequent law make a foreigner or any other description of persons citizens of the United States, nor entitle them to the rights and privileges secured to citizens by that instrument.

A State, by its laws passed since the adoption of the Constitution, may put a foreigner or any other description of persons upon a footing with its own citizens, as to all the rights and privileges enjoyed by them within its dominion, and by its laws. But that will not make him a citizen of the United States, nor entitle him to sue in its courts, nor to any of the privileges and immunities of a citizen in another State.

The change in public opinion and feeling in relation to the African race, which has taken place since the adoption of the Constitution, cannot change its construction and meaning, and it must be construct and administered now according to its true meaning and intention when it was formed and adopted.

The plaintiff having admitted, by his demurrer to the plea in abatement, that his ancestors were imported from Africa and sold as slaves, he is not a citizen of the State of Missouri according to the Constitution of the United States, and was not entitled to sue in that character in the Circuit Court.

This being the case, the judgment of the court below, in favor of the plaintiff of the plea in abatement, was erroneous.

II.

But if the plea in abatement is not brought up by this writ of error, the objection to the citizenship of the plaintiff is still apparent on the record, as he himself, in making oct his case, states that he is of African descent, was born a slave, and claims that he and his family became entitled to freed in by being taken by their owner to reside in a territory where slavery is prohibited by act of Congress--and that, in addition to this claim, he himself became entitled to freedom being taken to Rock Island, in the State of Illinois--and being free when he was brought back to Missouri, he was by the laws of that State a citizen.

If, therefore, the facts he states do not give him or his family a right to freedom, the plaintiff is still a slave, and not entitled in sue as a "citizen," and the judgment of the Circuit Court was erroneous on that ground also, without any reference to the plea in abatement.

The Circuit Court can give no judgment for plaintiff or defendant in a case where it has not jurisdiction, no matter whether there be a plea in abatement or not. And unless it appears upon the face of the record, when brought here by writ of error, that the Circuit Court had jurisdiction, the judgment must be reversed. The case of Capron v. Van Noorden (2 Cranch, 126) examined, and the principles thereby decided, reaffirmed.

When the record, as brought here by writ of error, does not show that the Circuit Court had jurisdiction, this court has jurisdiction to revise and correct the error, like any other error in the court below. It does not and cannot dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction here; for that would leave the erroneous judgment of the court below in full force, and the party injured without remedy. But it must reverse the judgment, and, as in any other case of reversal, send a mandate to the Circuit Court to conform its judgment to the opinion of this court.

The difference of the jurisdiction in this court in the cases of writs of error to State courts and to Circuit Courts of the United States, pointed out; and the mistakes made as to the jurisdiction of this court in the latter case, by confounding it with its limited jurisdiction in the former.

If the court reverses a judgment upon the ground that it appears by a particular port of the record that the Circuit Court had not jurisdiction, it does not take away the jurisdiction of this court to examine into and correct, by a reversal of the judgement, any other errors, either as to the jurisdiction or any other matter, where it appears from other parts of the tenor that the Circuit Court had fallen into error. On the contrary, it is the daily and familiar practice of this court to reverse on several grounds, where more than one error appears to have been committed. And the error of a Circuit Court in its jurisdiction stands on the same ground, and is to be treated in the same manner as any other error upon which its judgment is founded.

The decision, therefore, that the judgment of the Circuit Court upon the plea in abatement is erroneous, is no reason why the alleged error apparent in the exception should not also be examined, and the judgment reversed on that ground also, if it disclosed a want of jurisdiction in the Circuit Court. It is often the duty of this court, after having decided that a particular decision of the Circuit Court was erroneous, to examine into other alleged errors, and to correct them if they are found to exist. And this has been uniformly done by this court, when the questions are in any degree connected with the controversy, and the silence of the court might create doubts which would lead to further and useless litigation.

III.

The facts upon which the plaintiff relies did not give him his freedom, and make him a citizen of Missouri.

The clause in the Constitution authorising Congress to make all needful rules and regulations for the government of the territory and other property of the United States, applies only to territory within the chartered limits of some one of the States when they were colonies of Great Britain, and which was surrendered by the British Government to the old Confederation of the States, in the treaty of peace. It does not apply to territory acquired by the present Federal Government, by treaty or conquest, from a foreign nation. The case of the American and Ocean Insurance Companies v. Canter (1 Peters, 511) referred to and examined, showing that the decision in this case is not in conflict with that opinion, and that the court did not, in the case referred to, decide upon the construction of the clause of the Constitution above mentioned, because the case before them did not make it necessary to decide the question.

The United States, under the present Constitution, cannot acquire territory to be held as a colony to be governed at its will and pleasure. But it may acquire territory which, at the time, has not a population that fits it to become a State, and still govern it as a Territory until it has a population which, in the judgment of Congress, entitles it to be admitted as a State of the Union.

During the tine it remains a Territory, Congress may legislate over it within the scope of its constitutional powers in relation to citizens of the United State--and may establish a Territorial Government--and the form of this local Government must be regulated by the discretion of Congress, but with powers not exceeding those which Congress itself, by the Constitution, is authorized to exercise over citizens of the United States, in respect to their rights of persons or rights of property.

IV.

The territory thus acquired, is acquired by the people of the United States for their common and equal benefit, through their agent and trustee, the Federal Government. Congress can exercise no power over the rights of persons or property of a citizen in the Territory which is prohibited by the Constitution. The Government and the citizen, whenever the Territory is open to settlement, both enter it with their respective rights defined and limited by the Constitution.

Congress have no right to prohibit the citizens of any particular State or States from taking up their home there, while it permits citizens of other States to do so. Nor has it a right to give privileges to one class of citizens which it refuses to another. The territory is acquired for their equal and common benefit--and if open to any, it must be open to all upon equal and the same terms.

Every citizen has a right to take with him into the Territory any article of property which the Constitution of the United States recognises as property.

The Constitution of the United States recognises slaves as property, and pledges the Federal Government to protect it. And Congress cannot exercise any more authority over property of that description than it may constitutionally exercise over property of any other kind.

The act of Congress, therefore, prohibiting a citizen of the United States from taking with him his slaves when he removes to the Territory in question to reside, is an exercise of authority over private property which is not warranted by the Constitution--and the removal of the plaintiff, by his owner, to that Territory, gave him no title to freedom.

V.

The plaintiff himself acquired no title to freedom by being taken, by his owner, to Rock Island, in Illinois, and brought back to Missouri. This court has heretofore decided that the status or condition of a person of African descent depended on the laws of the State in which he resided.

It has been settled by the decisions of the highest court in Missouri, that by the laws of that State, a slave does not become entitled to his freedom, where the owner takes him to reside in a State where slavery is not permitted, and afterwards brings him back to Missouri. Conclusion. It follows that it is apparent upon the record that the court below erred in its judgment on the plea in abatement and also erred in giving judgment for the defendant, when the exception shows that the plaintiff was not a citizen of the United States. And as the Circuit Court had no jurisdiction, either in the case stated in the plea in abatement, or in the one stated in the exception, its judgment in favor of the defendant is erroneous, and must be reversed.

This case was brought up, by writ of error, from the Circuit Court of the United States for the district of Missouri.

It was an action of trespass vi et armis instituted in the Circuit Court by Scott against Sandford.

Prior to the institution of the present suit, an action was brought by Scott for his freedom in the Circuit Court of St. Louis county, (State court,) where there was a verdict and judgment in his favor. On a writ of error to the Supreme Court of the State, the judgment below was reversed, and the case remanded to the Circuit Court, where it was constituted to await the decision of the case now in question.

The declaration of Scott contained three counts: one, that Sandford had assaulted the plaintiff; one that he had assaulted Harriet Scott, his wife; and one, that he had assaulted Eliza Scott and Lizzie Scott, his children.

See complete transcript here

Chattel slavery is alive and unwell in the grate satan.

You’ll know that if you spend any time in a u.s.a. prison.

Inmates are tortured and killed if they don’t comply and do what they’re told.

Solitary confinement, food, water, and medication(s) withheld.

Several people dead just that way, in Waupun, in Wisconsin.

I know.

It was once a place that I didn’t call home.

Think Attica.

Think Gaza.

What changed the dynamic in those particular hell holes???

It wasn’t writin’ letters to the editor, or gittin’ out the vote.

It was takin’ hostages.

Unfortunately, in Attica and Gaza, the state(s) both invoked the Hannibal protocol, both in Palestine and New York.

And, if you say, well that’s different, it’s complicated, you must be stupid.

Like there ain’t no innocents in prison.

We all know better than that.

Or we should.

D.H. Lawrence figured out the essential American soul a long time ago.

We’re mean fuckers who are perfectly fine with our fellows being abused, and tortured, and killed in the guise of correction.

What they like to call rehabilitation.

What they’re accomplishing is turning flawed human beings into monsters.

If you think that many, even most, former inmates wouldn’t gladly put a knife to the throats of their tormentors, you haven’t got a clue.

I’ve been there.

I do.

I actually, completely, abhor violence.

What I’d like to see is a nationwide/worldwide general strike.

But, that won’t be nonviolent.

The Pinkertons, and the pigs, and the military, will bust our skulls, day and night.

Face the facts.

D.H. Lawrence got it right.

Lest we forget other ways to "kill" dissidents and radicals and revolutionaries:

Dissonance to Informational Control in Technological Society: Part 4

The establishment response to cognitive dissonance

https://neofeudalism.substack.com/p/dissonance-to-informational-control-ab0?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

He lists 20 of the Top 100 ways!